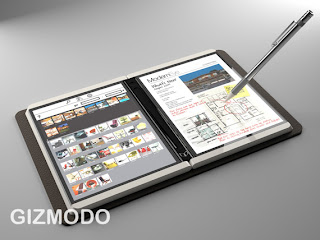

Gizmodo has broken the story on Microsoft’s top-secret skunkworks project for a revolutionary new tablet. Now, like the old auto-industry concept cars that were always chock-full of super-cool ideas but never actually came to market, this device may just be a clearinghouse for testing ideas rather than an early stage of a real product. Nobody outside Microsoft’s inner sanctums knows just yet. But the 2-minute demo video is, unequivocally, cool as hell. Go watch the video now. I’ll wait.

Gizmodo has broken the story on Microsoft’s top-secret skunkworks project for a revolutionary new tablet. Now, like the old auto-industry concept cars that were always chock-full of super-cool ideas but never actually came to market, this device may just be a clearinghouse for testing ideas rather than an early stage of a real product. Nobody outside Microsoft’s inner sanctums knows just yet. But the 2-minute demo video is, unequivocally, cool as hell. Go watch the video now. I’ll wait.It’s a “notebook” that’s really about the size of a spiral-bound notebook. But that’s not what makes it cool. It has dual 7” color LCD screens. But that’s not what makes it cool. What’s cool is how it’s being used. It resembles Microsoft Office OneNote in a lot of ways, which is a good thing. OneNote’s an excellent tool if you get the hang of using it, and it really shines when used on a tablet laptop. But the Courier takes the user interface to the next level by incorporating “flicks,” which are little finger-movements that mimic the way you’d actually flip through paper pages, post-it notes and other familiar, physical objects. And THAT’s a big deal. Why?

The challenge in developing a truly useful personal electronic notepad isn’t in the processing, it’s in the interface. We’ve had the technology for a long time to allow you to type in notes, to file away pictures and other documents, and to manage your calendar. But it’s always involved a keyboard and a mouse, which aren’t tools that lend themselves well to portability. OR, other controls have been substituted, but they were always small and clumsy, like on a smartphone. The iPhone made great strides in mixing portability with usability, but then again typing on its virtual keyboard is no joy, to the point where companies are creating slip-on hardware for folks who can’t get the hang of the iPhone virtual keyboard.

No, the challenge isn’t in making the apps work, it’s in making them work like what we’re used to. We’re used to jotting down notes, on paper, with a pen. We’re used to scraps of paper and Post-it notes and little sticky tabs and highlighters. And here’s the dichotomy – we ultimately hate those things, even though we’re used to them, because they’re so limiting. If you write notes in a notebook with a pen, they’re not very flexible. You can’t search your notes except with the old mark-I eyeball. You can’t share them with a classmate except by handing them the notebook (along with all of your other notes – hope you don’t need them). But you CAN doodle in the margins and you CAN go back and write a really small note above another line of text or draw an arrow from one part of the page to another and you CAN put a Post-it note on the page. If you stick a Post-it note on your tablet laptop, it makes it really hard to see your mouse pointer.

So there’s the challenge – making a replacement for pen-and-paper that’s better than pen and paper in every way, without significant drawbacks. Electronic “paper” like OneNote was nice because it let you insert additional lines to add more info if you were taking notes out of order (such as when your professor gets off-topic for a bit, then comes back around to his original point. As a professor I do this quite often. Must drive my students crazy.). But it relied on either using a stylus to “recognize” your handwriting, or a keyboard to type your notes, and it could be both hard to get used to and temperamental to operate. “Flicks” are the first step in making the interface “feel” like how we’d actually use a notepad or a day-planner. And that’s a Big Deal™.

I have no doubt that at some point, paper will be virtually replaced (pun intended). The

combination of better interfaces, ubiquitous personal computing devices, and flexible OLED (that's the picture at the right) will make it so easy to use “electronic” paper that it won’t make any sense not to – you’d never resort to plain paper on the off chance that the note you’re “just jotting down” will end up turning into a calendar entry or an email or a To-Do or a contact entry. The question that remains is one of when this will all happen. These advances sometimes race ahead and suddenly you have technologies you didn’t even know were in the works. More often, though, it seems to take a LOT longer than anyone expected. Take, for example, handwriting recognition and related technologies.

combination of better interfaces, ubiquitous personal computing devices, and flexible OLED (that's the picture at the right) will make it so easy to use “electronic” paper that it won’t make any sense not to – you’d never resort to plain paper on the off chance that the note you’re “just jotting down” will end up turning into a calendar entry or an email or a To-Do or a contact entry. The question that remains is one of when this will all happen. These advances sometimes race ahead and suddenly you have technologies you didn’t even know were in the works. More often, though, it seems to take a LOT longer than anyone expected. Take, for example, handwriting recognition and related technologies.According to an online history of Tablet PCs at WebProNews, “In the early 1980s, handwriting recognition was seen as an important future technology.” But nearly thirty years later, it still feels like a nascent technology when you try to actually use it. Granted, OneNote is better than the tools built into Windows XP Tablet Edition, which were a big step up from the tools built into the earlier PocketPC devices, but in all cases getting your handwriting reliably turned into text is a pain in the ass. Especially if you’ve got shitty handwriting, and increasingly it seems that most people do.

One workaround that OneNote uses is that it just doesn’t try to convert your writing to text unless you tell it to. This has the upside that it will continue to look no worse (or better) than when you first wrote it, but it also means that the capacity to search, spellcheck, copy/paste and otherwise manipulate the text is severely limited.

But advances continue to march ahead, and several are relevant to making devices like this an everyday reality as fully-realized, “peak” products that aren’t just limping along but are fully-functional in a way that makes them no longer mere gadgets, but something less. That’s right, something less. We don’t think about paper as a technology or pens as “gadgets.” They’re just pens. Even Post-it notes are long past the point where anybody thinks, “Wow, cool! A Post-it note!” They’re less than gadgets. They’re mundane. They’re bric-a-brac, items swirling around us as not much more than functional debris that we use almost without conscious thought except when we need it and don’t have it handy. THAT’s what these devices need to become. THAT will be the quantum leap forward that changes technological oddities into indispensible parts of our lives. I hope very much that I’m still young enough to appreciate and enjoy it when it finally happens.

If you love Onenote, you should head over the to www.iheartonenote.com, the world's one and only community site for OneNote lovers everywhere. If you join between September 22 and September 29, 2009, you will automatically be entered to win a $200 amazon.com giftcard.

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting, R.H.H. I'm signed up at that site now and will definitely take a look around!

ReplyDeleteYou just made me think -- having highly accurate OCR for my scores of old handwritten notebooks is not really important to me. I want text format files along with my scanned image files for -searching-, not -publishing-.

ReplyDeleteIf OCR can determine what I meant by a typical handwritten scrawl with only 20% accuracy, I cannot expect it to produce anything readable. But at the same time, if in nineteen out of twenty scrawls, the OCR can determine the meaning to within five words, it might well produce a useful index. An index with many false positives, but not so many as to make it unusable. Suppose I tell the index to compile a list, of locations, of occurrences, of a certain term. I suspect that the ratio of true positives to false positives in that list (it is meaningless to speak of negatives here) would not vary with the size of that list. If the ratio is not too low, then OCR weakness cannot be to blame for unfeasibly long search results. (More likely culprits: searching for the word 'of', or searching on too huge a corpus for your term). When searching my own notebooks, I believe conjunctive queries would be more useful than disjunctive queries (personal use case here), and (happily) conjunction of search terms increases the quality of the result.

The problem of false negatives (locations of the term which were ignored by the index) is a distinct problem. First, there are use cases for which this problem is not a usability issue. Second, the "generosity" of the OCR that accounts for the false positives makes the likelihood of false negatives negligible in most actual use cases. (I'm tempted simply to simply say: "The given conditions of the OCR causes the issue of 'false negatives' to be of neither practical concern, nor of theoretical interest" -- but it is too late at night to prove that to myself, much less make an argument for the case.) (Though if I could prove it to myself, I might be bold to just state it without argument.)

--

You see what happened? You do me the favor of get me thinking about an idea, and I pay you back with making some long tedious argument for a thesis -- which you should read as nothing more than my working out the idea. No good deed goes unpunished! :-)

Seriously, leaving theory aside, it seems to be that ... yeah! even shitty[1] OCR can be fine for searching. And if it is a sensible idea, I am probably not the first to realize it, but you sparked me into thinking it. And if the idea's a dud, the fault's mine alone.

Mike:

ReplyDeleteI forgot the footnote.

[1] Sometimes the 'right' word can be a 'rude' word. Feel free to obfuscate.

Largo - I don't necessarily disagree that partially-successful OCR is better than none at all if the success rate is high enough, but I still think anything less than 99+% is a barrier to mass adoption. People are used to, and comfortable with, writing stuff down, sharing it, filing it, reading it later, and in all cases having it be more-or-less 100% readable. Any technology that tries to "improve" on good ol' pen-and-paper needs to add functionality (like search, easy transmission, organization, transformation (into calendar entries, task items, contact info, etc.) and so forth, while still maintaining the two things people are used to: reliability (the materials are highly-available and therefore always accessible, plus you can be fairly certain that they'll be readable by you or others) and ease-of-use (once you learn to write, you can use pretty much any pen and any style of paper to do it. You don't want to have to constantly re-learn how to use these simple and indispensable tools because there's been a version upgrade or some new hardware released). It's a given that they're giving up the third existing feature - that of being extremely inexpensive. A vast supply of paper and pens can be purchased for $20 - the "paper-replacement" technology will certainly cost much, much more than that, at least for a while. If the first two factors are sufficiently enhanced by sacrificing the third, it's likely a lot of people will opt to make that trade-off, but there are definite limits in what people will accept (as demonstrated by the slow adoption of the Tablet PC, I think). Less-than-optimal OCR, in my opinion, falls in the category of being outside those limits.

ReplyDeleteThat's my take, anyway. It may be that algorithmically, your thesis could be put to work in making "partially-successful OCR" sufficiently acceptable by letting it guess what the user most likely wants to see, but historically my experiences with that kind of technology hasn't been completely satisfying.

Either way, it's great to be at a point where this level of debate is even appropriate, given how long it's taken technology to come even as far as it has.

I think your take is is entirely correct. I was enthused by the prospects for a very narrow market (me) (even if I have to hack it myself), and I am an habitual thesis writer, even in casual communication. I would not describe myself as a good correspondant!

ReplyDeleteAll that aside, perhaps you missed my point when you speak of "letting [OCR] guess what the user most likely wants to see." Historically, my experiences with that have been far from completely satisfying--when it comes either to block transcription or to command recognition (where even short delays can be a usability disaster)--and what I propose would not help that.

But if I consider my collection of notes as a resource to be datamined, then I'll be most happy with a system that doesn't guess. I could be happy with an index whose typical entry has nine bogus page numbers for every correct page number. A very different kind of use case scenario.

Or perhaps you didn't miss the point (not that it matters much). Anyhow, I will refrain from writing a thesis on use-case psychology!

--

By the way, just in case blogger does not notify you of activity on old posts:

http://virtualvellum.blogspot.com/2009/09/lightspeed-is-relatively-complicated.html

http://virtualvellum.blogspot.com/2009/09/im-not-left-handed-either.html

(It's been a long night.)

Thanks, Mike!

ReplyDelete